Designers

Happy Birthday, Gangsta Boo

Wendy Brandes

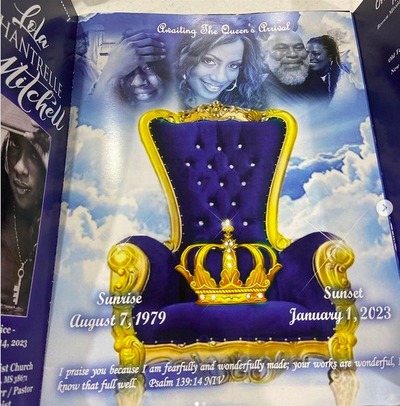

My irrepressible and irreplaceable friend Lola Mitchell — aka Gangsta Boo of the trailblazing rap group Three 6 Mafia — would have turned 44 today. But, tragically, Lola died on January 1 in her hometown of Memphis.

As I said in my previous blog post, I started writing a tribute to Lola the day I got the news, but I couldn’t finish it then. It all seemed unreal. A lot of people close to Lola had died much too young, including DJs Speakerfoxxx (35 years old) and Furoche (27, victim of an unsolved hit-and-run), as well as two of her Three 6 Mafia bandmates, Lord Infamous (40) and Koopsta Knicca (40). A few years earlier, her father’s death had hit her hard too. Lola and I had discussed those losses, but Lola herself dying? It never crossed my mind. She was such a life force. She’d overcome so much. She had so much passion and ambition still. Did she like to party? Sure, but not so much that she felt compelled to do it around me.

Unfortunately, the dangerous opioid fentanyl now taints a wide variety of party (and other) drugs, and it proved fatal for Lola on New Year’s Eve. If you have ever taken a drug from an unregulated or unknown source and/or might do so — and this includes pills, even a single Xanax or Adderall that your friend got online — keep some over-the-counter Narcan spray around to reverse a fentanyl overdose. I’ve been meaning to get some myself in case I ever come across someone who needs it. In fact, in honor of Lola, I just put an end to my Narcan procrastination in the midst of writing this sentence and ordered it. (You can get it free in New York State.) Harm reduction is the name of the game, not judgment.

Lola and I bonded over what an endless slog it can be to get anywhere in a creative field. Even though I design fine jewelry and she rapped, we understood each others’ frustrations, and how it felt to achieve a certain level of respect in an industry without become a household name or feeling financially secure. We’d joke about both of us being a “most-known unknown,” riffing off the title of a Three 6 Mafia album (one that Boo wasn’t on). That said, real rap aficionados knew of Lola, who had shot to fame as a teenager in the 1990s as the first of two female members of Three 6 Mafia. To those fans, she was such a legend that folks couldn’t believe their eyes when they saw her on the street or in a bar or waiting in line for the Ferris wheel at the Santa Monica Pier.

Her Instagram display name was “Thee Gangsta Boo” because that was what the fans always asked: “Are you THEE Gangsta Boo?!” In Memphis, she was such a hometown hero that, in 2012, when she arrived at the Memphis airport without any ID (or luggage!) on her, she still got on the plane because all the security people knew who she was. After all, one of her nicknames was "Queen of Memphis."

But that didn't mean she was where she wanted to be professionally. Even last year, as Lola started getting name-checked by new rap stars like Latto and Glorilla, she and I still said to each other that people would appreciate us most “some day” — meaning when we were no longer around to enjoy it. Just weeks before her death, in an interview with Billboard, she reflected on this status:

“Well, right now, just still getting my recognition and my newfound accolades and when other ladies pop out, it’s always like, ‘Wow, this person sound like Gangsta Boo,” or, “Why is Boo’s name not mentioned enough?’ But at the same time, I still have so much work to do.”

As predicted, in the wake of her death, tributes poured in from fans, music-industry giants like Missy Elliot and Drake, and the media. The Washington Post said, “Gangsta Boo’s Southern hip-hop influenced a nation of female rappers.” She was covered by the New York Times, the L.A. Times, USA Today, Rolling Stone, Variety, NPR, the Source, Complex, the Guardian, People magazine, Billboard, and Memphis’s Commercial Appeal. This piece from Stereogum is one of my favorites. In the midst of all this, I kept expecting her to call — she preferred calling to texting — and say to me, “Maaaaane, can you believe this?!” (The only major institution that didn’t pay respect to Lola was the consistently racist and sexist Recording Academy, which left her out of the Grammys’ tribute section a month after her death.)

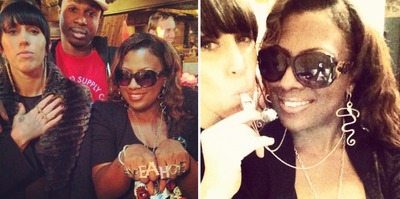

Many of the articles included photos of her wearing my jewelry — which I knew she would have been thrilled to point out to me. Over the years, I had enjoyed giving her gifts of silver jewelry, and she was always so diligent about “product placement.” She thought about it way more than I did! Meeting 50 Cent? Here’s Wendy’s jewelry.

Billy Bob Thornton? Let’s make sure the borrowed gold necklace is in the shot.

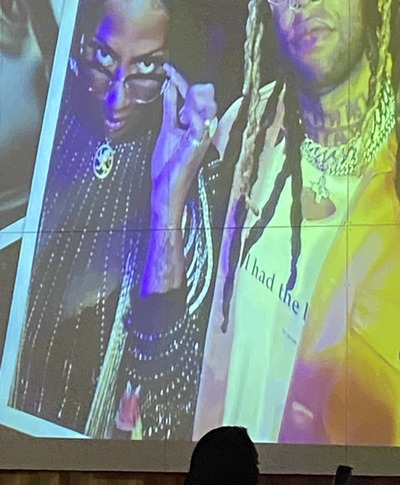

And she certainly came up with an unforgettable publicity shot featuring the nameplate necklace I made for her.

Lola’s policy was that if she was going somewhere — whether that was figuratively, career-wise, or literally, to the stage — I was going with her. I would have been happy to be the quiet, supportive entourage member, but that wasn’t always an option. If Lola was going live on Shade 45, satellite radio’s big hip-hop station, she was going to borrow a pile of gold jewelry, take me with her to the studio, mention me on air, and coax me to squeak an embarrassed “hi” into the mic. Complex called her “Memphis’ Grand Connector” and many of the people who eulogized her at her funeral — and at the massive tribute party the night before the funeral — spoke of her passion for collecting and connecting people. If you grabbed her attention and met her approval, you were officially part of her network.

That’s how I met her in 2011-2012. I had heard her on a track called “Throw It Up” with Yelawolf and Eminem, and I started following her on Twitter. I thought she was so funny and provocative there that I slid into her DMs to offer her some silver rings as a no-strings-attached gift. She insisted on a phone conversation first — one that I tried to escape because I was like, “What is she going to want with some 12-years-older white woman from New York.” Next thing I knew , she was BFFs not just with me but with MrB (even though he thought her compliment of OG meant “Old Guy” instead of “Original Gangsta"). When she came to New York, I put her up in my parents’ vacant Manhattan apartment, because, I thought, why not? Even though I was meeting her for the first time ever! She never stopped telling people about that.

In return, Lola always said that when she could afford it, she’d buy gold jewelry from me. And last year, after she appeared in a reality show wearing gold pieces she borrowed from me, she bought two of them — my Eleanor lion pendant because she was a Leo, and my Borgia poison ring — as soon as the money hit her bank account. (For anyone who watched that show, her worry about her jewelry box was legit. I had sent her a lot of pieces!) She’d always been casual with the silver jewelry — she knew if she lost it, I’d replace it — and she alternated the silver with her collection of big costume jewelry, especially for performances. So, when she told me the hinge of the now-purchased poison ring needed a tune-up, I said, “Send it to me and I’ll fix it,” figuring she had plenty of other stuff to wear. She didn’t reply for a few days. When I reminded her, she said she couldn’t be without the ring that long. No, not even if we used FedEx and I promised to get the ring back to her in a week. I was bemused by that until I saw her 2022 holiday photos in a slideshow at the pre-funeral party. She was wearing the Leo necklace and poison ring in every picture. Whether she was performing or in her pyjamas at home. There was something about that that floored me. With the exception of engagement rings, it’s unusual to see someone wearing the same statement pieces daily for such a long stretch. Maybe I’m reaching for solace or meaning, but I feel like she wore those pieces not because of their aesthetics or value, but because they were a symbol of our friendship, as well as a long-awaited moment of shared success.

That whole night, I couldn’t stop thinking, “Oh, I can’t wait to ask her about this.” It wasn’t until her coffin was carried past me at her funeral the next day that I fully understood that she was gone. You know, a lot of people say they don’t “do” funerals, even to offer condolences to the survivors. But I was glad I went, not just to show her family my support, but because it was the only way I achieved any acceptance of her loss. (The acceptance still wavers at times.) I also got to hear people describe her as a bright light, as the energy in the room, as a devoted friend and family member. I got some good inspiration too: Like Lola, I now want to make my grand exit from this world with people dancing to Gangsta Boo’s big strip-club anthem, “Where Dem Dollas At.” Leave ’em laughing!

I'll end with Lola's own words from a 2012 interview with Jimmy Ness, during which she was asked how she would want to be remembered. She said:

"I just want people to know that I’m a really hard worker. I’m human just like everybody else. I write all my own music. I’ve helped other people come up with concepts. I’ve helped put a lot of people on. I just want to be respected. When it’s all said and done, I want to be remembered as Gangsta Boo from Three 6 Mafia. The first lady of Three 6 Mafia. The first lady of crunk music. The first lady who brought a platinum plaque back to Memphis. The first lady who brought a gold plaque back to Memphis. I’m the only female rapper in Tennessee that has ever did that and probably I will be the only one that ever will. I just want to be known as someone that put her heart into her music and who really really appreciated her fans. Because if it wasn’t for my fans, like I said, I definitely would not still be doing this. My fans are my motivation. I love my fans."